CHICAGO — A federal appeals panel has undone a $44.7 million verdict in favor of a man who was shot by an off-duty Chicago police officer.

Michael LaPorta sued the city after his friend, Patrick Kelly, shot him in the head, leaving him with severe, permanent disabilities. LaPorta argued that although Kelly was off duty, the shooting resulted from a failure of city policy. LaPorta's lawyers argued Kelly’s likelihood to commit such an act should’ve been known.

Following the jury verdict, the city asked U.S. District Judge Harry Leinenweber to undo the jury verdict. The judge denied that motion, prompting the city to appeal.

Antonio Romanucci Romanucci & Blandin

| uwalumni.com

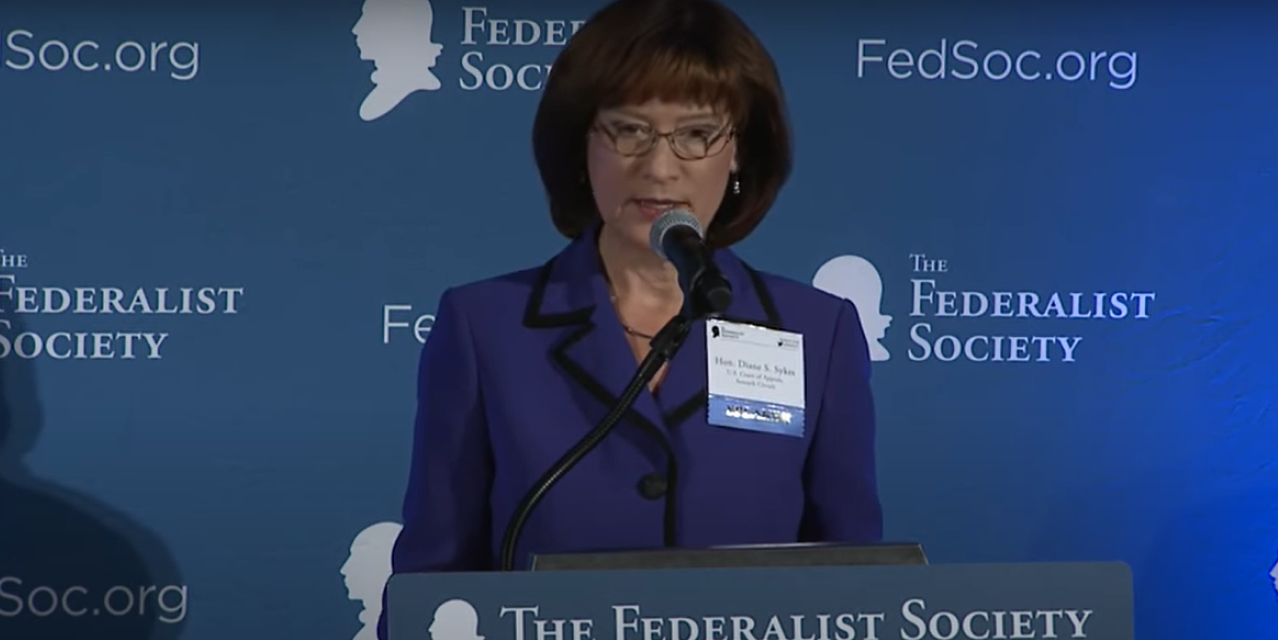

Chief Judge Diane Sykes of the U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals wrote the opinion on the city’s appeal, issued Feb. 23; Judge Michael Kanne concurred. When the appellate judges heard arguments on Dec. 10, 2019, their three-judge panel included current U.S. Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

Barrett did not participate in the decision.

According to Sykes, the shooting happened “during an argument at the end of a night of drinking together” in January 2010. She said LaPorta’s “theory of the case was novel” and that although his “injuries are grievous … his legal theory for holding the city liable is deeply flawed.”

LaPorta framed his lawsuit on a 14th Amendment due process right to bodily integrity. The argument began with Kelly hitting his own dog in his home. LaPorta objected and said he was leaving when Kelly fired, resulting in traumatic brain injuries. LaPorta can no longer walk or use his right arm, is blind in one eye and deaf in one ear.

As the city argued to dismiss the complaint on the grounds “it had no constitutional duty to protect LaPorta from Kelly’s private violence,” Leinenweber allowed the case to proceed. LaPorta testified to Kelly’s “history of civilian and internal disciplinary complaints” and the city’s failure to use a system to identify police officers who could pose problems, to adequately investigate and discipline offices and fostering a “code of silence” that stifled misconduct reports.

Ultimately, the panel explained, LaPorta failed to demonstrate how the city deprived him of a federal right. His argument failed, it continued, because the purpose of the 14th Amendment’s due process clause is protecting people from the government, not from each other.

“It’s undisputed that Kelly was not acting under color of state law when he shot LaPorta,” Sykes wrote. “Kelly’s actions were those of a private citizen in the course of a purely private social interaction. This was, in short, an act of private violence.”

In order to succeed, the panel said, LaPorta would have to establish the city had custody of LaPorta or that the city specifically placed him in danger, neither of which is pleaded. Sykes said the situation is similar to, among other examples, a 2001 Seventh Circuit opinion in Latuszkin v. City of Chicago in which a district court dismissed a complaint from a woman whose husband died as the result of being struck by a car driven by an intoxicated off-duty police officer.

Sykes said Leinenweber erred in overlooking the applicability of the 1989 U.S. Supreme Court opinion in DeShaney v Winnebago County Department of Social Services, which the city used to argue it doesn’t have a constitutional duty to protect against private violence, and focusing only on the municipal liability established in its 1978 opinion in Monell v. Department of Social Services.

“LaPorta’s case is tragic. His injuries are among the gravest imaginable. His life will never be the same,” Sykes wrote. But the Constitution “imposes liability only when a municipality has violated a federal right. Because none of LaPorta’s federal rights were violated, the verdict against the city of Chicago cannot stand.”

The panel reversed Leinenweber’s ruling and remanded the case with instructions for judgement in favor of the city.

LaPorta has been represented on appeal by attorneys Antonio M. Romanucci and Bryce T. Hensley, of the firm of Romanucci & Blandin, of Chicago; David R. Rudovsky, of Kairys, Rudovsky, Messing, Feinberg & Lin, of Philadelphia; Carolyn Shapiro, of Chicago; Robert S. Peck, of the Center for Constitutional Litigation, of Washington, D.C.; and Michael W. Rathsack, of Chicago.

The city of Chicago has been represented by corporation counsel from its Department of Law.