CHICAGO — A federal appeals panel has punted on answering whether plaintiffs should be limited in demands for payouts under Illinois’ biometrics privacy law, handing off to the Illinois Supreme Court the issue of limiting potentially crippling penalties for employers facing class action lawsuits.

A three-judge Seventh Circuit panel heard arguments in September regarding whether they should become one of the first judicial bodies to restrict the reach of the Illinois Biometric Information Protection Act.

In early 2019, attorneys with the Chicago firm of Stephan Zouras sued White Castle in Cook County Circuit Court on behalf of named plaintiff Latrina Cothron, who worked as a restaurant manager and had been employed by White Castle since 2004. She accused White Castle of violating the law by requiring workers to scan fingerprints without first receiving notices and giving consent.

White Castle removed the complaint to federal court and moved to dismiss, arguing only the first fingerprint scan under the 2008 law should constitute a violation. If that interpretation is upheld, it would end Cothron’s claim as untimely.

U.S. District Judge John Tharp rejected the motion, but allowed an appeal to the Seventh Circuit on the question, because White Castle’s theory would limit damages to just one injury claim per employee, not hundreds or even thousands of claims each based on every individual fingerprint scan.

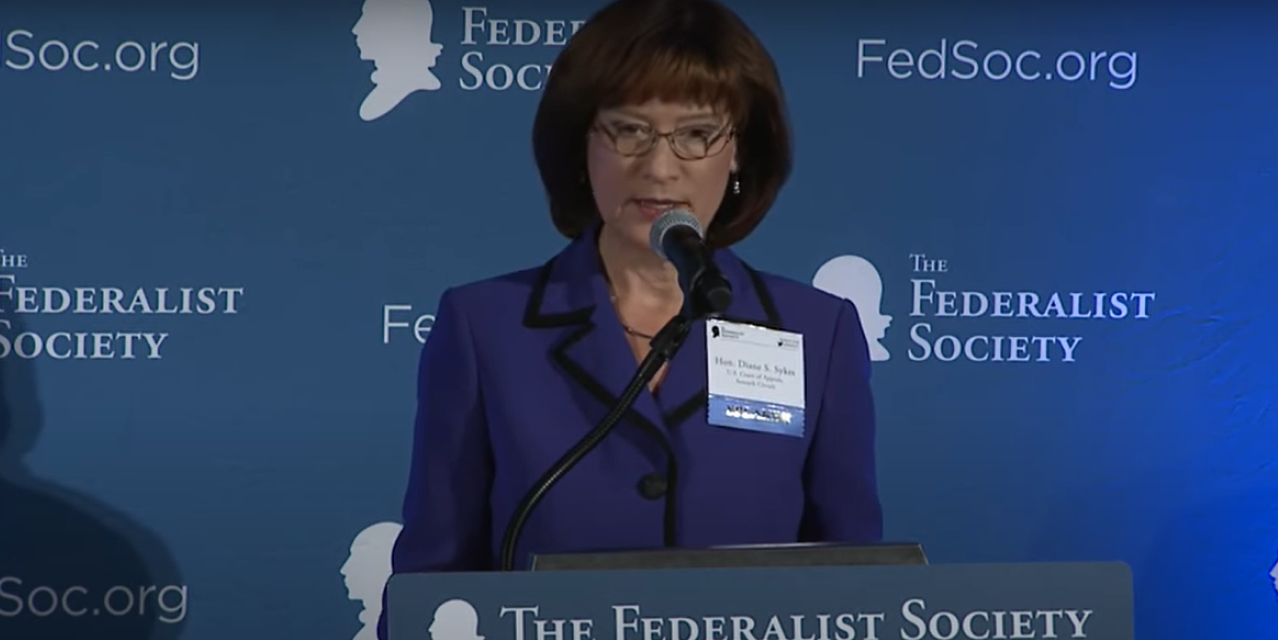

Attorney Melissa Siebert, of the firm of Shook Hardy and Bacon, of Chicago, represented the chain before Judges Diane Sykes, Frank Easterbrook and Michael Brennan. Sykes wrote the panel’s opinion, issued Dec. 20.

The panel pointed to its own 2013 opinions in Reliable Money Order v. McKnight Sales, which established each transmission of an unsolicited fax is its own violation, and Pippen v. NBCUniversal Media, which held that certain privacy violations occur only with initial publication of defamatory material.

“Repeated transmissions of the same biometric identifier to the same third party are not new revelations,” Sykes wrote. “White Castle argues, not unreasonably, that an actionable disclosure occurred only the first time Cothron’s fingerprint was transmitted.”

But Cothron noted BIPA bans “redisclosure” of biometric data, supporting her position that each scan is a new violation. White Castle said “redisclosure” applies to “a downstream disclosure carried out by a third party to whom information was originally disclosed,” Sykes wrote. “That reading is consistent with the term ‘redisclose’ as used in other Illinois statutes.”

The panel said there may be room to determine multiple fingerprint scans aren’t any worse than just one. But it also noted that repeated data collections and transmissions to a third-party vendor — even the same fingerprint sent to the same vendor — could increase risk the data is mishandled or misused.

“Beyond their arguments from text and precedent, both Cothron and White Castle maintain that the other’s position would produce untenable consequences that the General Assembly could not possibly have intended,” Sykes wrote.

On one hand are potentially “staggering” damages for businesses. On the other is that a “first-time-only reading” of BIPA means the law gives no incentive for a violator to change its policy to comply.

The panel said it can certify state-law questions to a state’s supreme court if the answer would determine the outcome of a case, which would be true here because a finding in favor of White Castle would end Cothron’s complaint. The Illinois Supreme Court, the panel continued, allows certified questions from the Seventh Circuit if none of its preceding cases resolve the outcome, which Sykes explained also is true in this matter.

However, Sykes continued, the panel also must find itself “generally uncertain” about the answer before punting, and “there are reasons to think that the Illinois Supreme Court might side with either Cothron or White Castle. A wrong answer may also transcend the Act and implicate fundamental Illinois accrual principles on which only the state’s highest court can provide authoritative guidance.”

Finally, the panel also noted the BIPA is a unique state law and one the Illinois Supreme Court has interpreted in other cases. Any proceedings are stayed while the top court tackles the question.

A number of other BIPA-related cases have been placed on hold, awaiting an answer on the key question. It is unclear whether judges hearing those cases will now similarly await an answer from the Illinois Supreme Court before allowing proceedings to resume in the cases before them.