CHICAGO — A federal appeals panel says a federal judge misinterpreted its decision regarding the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act, ending a string of cases in which plaintiffs’ lawyers had used that decision to extract their class actions from federal court and place them back into Cook County and other Illinois state courts, considered by many to be more plaintiff friendly.

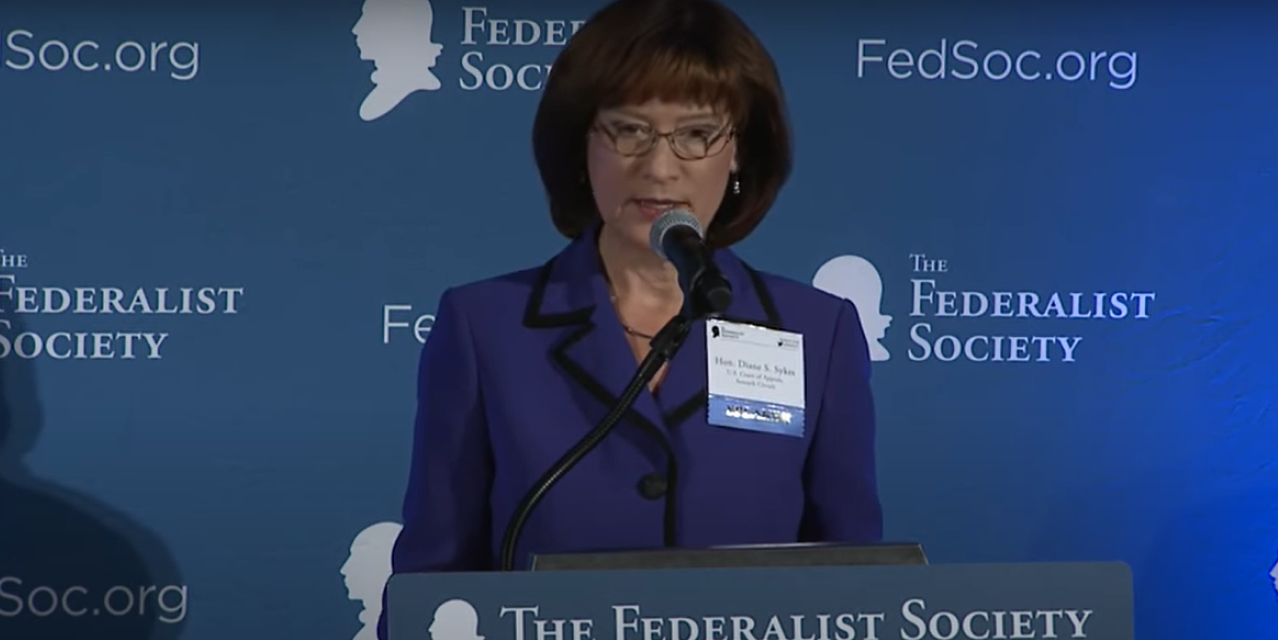

Seventh Circuit Chief Judge Diane Sykes wrote the opinion; Judges Diane Wood and Michael Brennan concurred.

Melissa Siebert

| Shook Hardy & Bacon

The opinion is the latest development in an ongoing dispute in numerous cases over the proper venue for BIPA complaints — federal or state court — and the legal obligations facing companies that collect personal data, such as fingerprints and facial scans.

Fox and her lawyers, with the firm of Stephan Zouras LLP, of Chicago, had filed the class action originally in Cook County Circuit Court, accusing the company of violating the Illinois BIPA law for requiring employees to scan their handprints to verify their identities when punching the clock for work shifts.

The lawsuit, like many filed under the BIPA law, centers on claims that the company wrongly required the handprint scans without first obtaining permission from the employees to scan their biometrics, and that the company did not provide the notices allegedly required by the law, or post a so-called retention schedule disclosing why the scans were conducted and what the company was going to do with the scanned information.

Each of those claims are covered under different sections of the BIPA law, referred to in court documents as Section 15(a) – the portions of the suit pertaining to retention and disclosure - and Section 15(b), the portions of the complaint alleging failure to obtain consent.

Under the BIPA law, the company could be on the hook for damages of $1,000-$5,000 per violation, with each violation potentially counted as each time an employee scanned their handprint.

Dakkota removed Fox’s lawsuit from Cook County court to federal court, then sought dismissal by arguing the claims should not be allowed because they allegedly conflicted with the federal Labor Management Relations Act.

Before those Labor Management Relations Act claims could be fully aired, U.S. District Judge Charles Kocoras split the case in half, and sent the portion of the lawsuit dealing with Dakkota’s alleged failure to publicly disclose its data retention policy back to Cook County court, as requested by the plaintiffs.

He then dismissed the remainder of the lawsuit.

In making that decision, Judge Kocoras cited a May decision from the Seventh Circuit, which appeared to split such cases in half.

While claims under Section 15(b) could be heard in federal court, claims under Section 15(a) may not, because they may not involve any real injury against the plaintiffs, according to the Seventh Circuit’s decision in the case Bryant v Compass Group USA.

The question of whether a legal injury is real or not, however, is not a problem in Illinois courts, as the Illinois Supreme Court has ruled plaintiffs don’t need to show how a company’s actions actually harmed them in order to press their BIPA claims in state court.

Kocoras’ decision lines up with those of several other federal judges, who have reached similar conclusions in allowing plaintiffs and their lawyers to keep at least portions of their class action claims alive and kicking in Cook County and other state courts, when defendants had sought to keep the case in federal court to challenge it with various legal theories under federal law.

Dakkota appealed Kocoras’ decision.

The Seventh Circuit judges said it would be a misreading of their decision in Bryant to presume that all allegations brought under Section 15(a) automatically warrant a return ticket to state court.

“The remand order was a mistake,” Sykes wrote.

In the Bryant case, the judges ruled the company’s alleged violation of BIPA Section 15(a) should be treated merely as a procedural failure, and not a concrete personal legal injury.

In Fox’s suit, however, the plaintiffs in bringing allegations under Section 15(a) also leveled allegations concerning Dakkota’s retention and distribution of her data, amounting to a potential “invasion of a legally protected privacy right” under BIPA, Sykes said.

So, in this case, federal court was the proper venue.

According to the panel, Fox said Dakkota didn’t get her written consent to collect and store biometric information, illegally gave the information to third parties, including a data center, and didn’t develop, disclose or implement a plan for destroying personal data. She said the company still has her data on file despite her employment ending in 2019.

Sykes explained the matter is complicated because Fox’s alleged injury is intangible. The panel pointed to the case of Miller v. Southwest Airlines. In that case, unionized airline workers had brought a class action against the airline, alleging Southwest had similarly violated BIPA in the way it required workers to scan fingerprints when punching the clock.

In that case, the court decided the class action did not belong in state court, and ruled the dispute amounted to a collective bargaining subject. However, the panel also said the federal Railway Labor Act meant those claims belonged before an adjustment board, not in a class action.

The appellate judges noted Fox also was represented by a union during her time with Dakkota.

The panel also looked at a 2019 U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals opinion in Patel v. Facebook, a BIPA class action accusing the social media giant of violating BIPA by scanning the faces of people in uploaded photos. That case recently settled for $650 million.

The Ninth Circuit, based in San Francisco, determined those plaintiffs also had standing in federal court because they alleged actual or material risk of harm to their privacy interests.

The Bryant case was different, Sykes explained, because it didn’t include a union argument or a condition of employment. Rather, it centered on allegations against the operator of vending machines at a workplace, which required employees to scan fingerprints to purchase items.

While the plaintiff in that case could sue in federal court over being deprived of the right to make informed choices about her data, she didn’t suffer a personal injury due to a lack of public data retention and destruction policies.

Fox’s complaint, however, was farther reaching.

“An unlawful retention of biometric data inflicts a privacy injury in the same sense that an unlawful collection does,” Sykes wrote, adding that biometric identifiers “are immutable, and once compromised, are compromised forever.”

The panel sent Fox’s complaint back to federal court, instructing Judge Corcoras to determine if it is pre-empted by the LRMA, as Dakkota has claimed in its defense.

Dakkota has been represented by attorneys Melissa A. Siebert, Erin Bolan Hines and Jonathon M. Studer, of the firm of Shook, Hardy & Bacon LLP, of Chicago.