An antitrust lawsuit unraveled last week when a federal judge ruled in favor of a Chicago-area dress shop accused by one of its competitors of stitching together a monopoly on the local prom dress market.

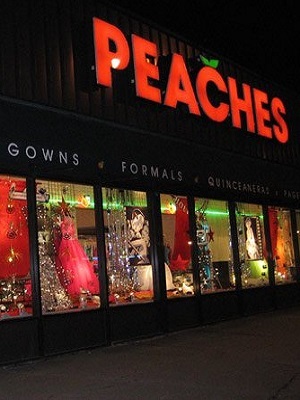

Hannah’s Boutique Inc., of Palos Park, filed suit against rival dress shop Peaches Boutique in U.S. district court. The suit charged Peaches with conspiring with dress designers to jilt competing boutiques and make Peaches those designers’ one and only Chicagoland retailer.

Federal charges included attempted monopolization, conspiracy to monopolize, monopolization, concerted refusal to deal, unreasonable restraint of trade and exclusive dealing. Judge Amy J. St. Eve granted a motion by Peaches for summary judgment, finding there was not enough evidence to support the antitrust charges.

According to the lawsuit, Hannah’s, which opened in 2009, is a 2,600-square-foot store specializing in prom and homecoming dresses. Peaches sells similar merchandise. It opened with 2,400 square feet in 1985 and expanded over the years to its current size of 25,000 square feet. Peaches carries more than 20,000 dresses it sells in store and online, according to court documents.

In the suit, Hannah’s said that Peaches conspired with 16 designers of high-end formal dresses to cut Peaches’ competitors, including Hannah’s, out of the market. The plaintiff said Peaches repeatedly asked the designers not to supply their dresses to specific competing stores.

Much of the suit’s argument rested on showing that Peaches has enough market power in the Chicago market to build a monopoly, according to the court’s opinion. The opinion noted that Seventh Circuit precedent holds that for antitrust charges to carry weight, the defendant should have at least 17 percent market share in its geographic area.

According to evidence submitted in the case, there are 42 department stores and 56 specialty retailers besides Peaches and Hannah’s that sell prom dresses in the Chicago market. An expert witness on behalf of Peaches estimated the store’s market share is somewhere between 2 and 9 percent.

In 2012, the suit says, Peaches invited a number of designers to a meeting at the Atlanta Prom Market. None of Peaches’ competitors were invited to the meeting, where one of Peaches’ owners distributed a handout of “industry concerns.” Soon after, 15 designers, including seven who had previously sold dresses to Hannah’s, rejected or canceled orders placed by the store.

Though the designers may have independently been swayed by Peaches’ request for help in protecting its sales territory, the court found no evidence that they conspired together to engage in a group boycott to restrain trade, and dismissed all of the antitrust charges.

In addition to the antitrust claims, Hannah’s claimed interference with contract, interference with prospective economic advantage, civil conspiracy and violation of the Illinois Consumer Fraud and Deceptive Practices Act. The court dismissed these state-level claims as a matter of procedure, but did not issue an opinion as to whether there was a basis to support them.

“The Court’s ruling only addresses Defendants’ actions from the perspective of federal antitrust law,” St. Eve wrote. “Whether Plaintiff has valid business tort claims under Illinois state law for Defendants’ alleged interference with its commercial relationships or for unfair competition is a different question.”